What Leaders Have Told Us: How we analyse our findings

Writing and publishing a book in super fast time based on the interviews and conversations we’ve been having with global leaders since launching the Thinking the Unthinkable project in 2014 was a significant challenge.

Authenticating and substantiating the qualitative data we have collected from many leaders and other sources was a critical part of the process.

At the time of writing there are transcripts from more than 100 formal interviews and nine contemporaneous notes of conversations.

Additionally there are transcripts from about 40 public events and interviews on radio and TV programmes, plus some 60 handwritten notebooks from the conversations and chats our Directors Nik Gowing and Chris Langdon have had with leaders.

Considerable resources have been used to ensure the accuracy of the data. All transcripts have been re-checked against the original audio recordings in 2017-2018.

This dataset is being constantly increased and updated. A total of 2,495 pages of text have been analysed thus far. In social science research this is regarded as a large, ‘meaty’ dataset by any standards.

We set out to enrich and substantiate our initial findings published in February 2016 and to test our original working assumptions. We analysed the data using a combination of text mining, discourse and content analysis.

We then used multiple analytic methods to complement each other. This process is known as triangulation.

The software programme was NVivo version 12 Plus. The NVivo tools enabled us to see ‘the big picture fast’. Through a combination of its automatic insight features and our own interpretation, we gained rich, granular insights from our dataset.

To authenticate and peer review our analysis, we consulted Dr Christina Silver, Co-Founder and Director of Qualitative Data Analysis Services (QDAS).

A Research Fellow at the University of Surrey, she helped us challenge our own assumptions, plan the data analysis and then achieve our research aims through NVivo.

Christina emphasised the importance of the initial planning phase in order to identify the themes for analysis and subsequent manual coding. This would ensure our findings were robust, and that we got the most out of NVivo’s processing capabilities.

She is continuing to provide ongoing advice to Thinking the Unthinkable on the use of NVivo for our data analysis.

The large and diverse data sample allowed us to increase the generalisability, external validity and reliability of our initial findings.

Our project researcher, Didi Ogede began by inputting and then manually coding 20% of the transcripts. She identified the words and phrases which reflected more than 60 key themes about leadership which we wanted to test against our original, more subjective findings published in February 2016. These had identified nine priority emerging themes.

In a second phase of this process of evaluation, Didi then used NVivo’s pattern-coding features to identify the same themes among the remaining 80% of the dataset.

She did not blindly accept NVivo’s assessment. She reviewed all the data segments it suggested. Based on her initial careful coding, she then refined the results to ‘clean’ the data and ensure greater accuracy.

During the first round of analysis, coding focused on 26 themes. The results corroborated the nine key concepts we first identified in February 2016. In doing so they substantiated the overarching assertions and conclusions about the new vulnerabilities of leadership which we made at that time.

Our next stage of updated and statistically rigorous analysis concluded in April 2018. It identified ‘short- termism’ as a dominant concern among leaders. More than 80% of our sample (103 interviewees) mentioned it.

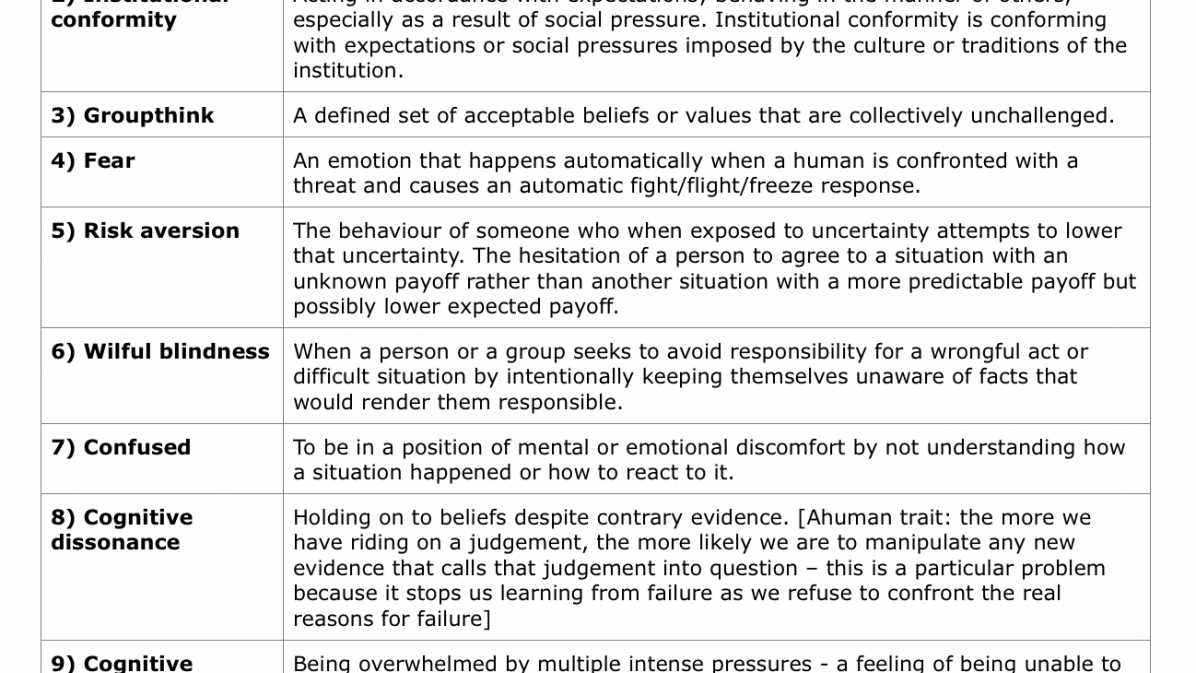

In addition, ’institutional conformity’ and ‘groupthink’ were highlighted by more than 65% of our sample. The themes of ‘fear’, ‘risk aversion’ and ‘wilful blindness’ were also frequently mentioned by 58–62% of the sample.

‘Confused’, ‘cognitive dissonance’ and ‘overload’ were also volunteered frequently (by between 46–54% of the sample).

‘Fear of career-limiting moves’ was raised by more than 40% of the sample. ‘Behaviour’ was referred to by more than 50% of our sample. Importantly, this indicated that leaders acknowledge certain behaviours and attitudes among themselves and within their organisations.

Only three out of the original nine themes did not emerge in the top 10 of our systematic re-analysis. They were ‘overwhelmed’, ‘reactionary mindsets’ and ‘denial’.

The latter two were not included in the initial coding (of 26 themes). ‘Overwhelmed’ was very close to making the top 10.

A second round of data analysis is the backbone for this book. It included all transcripts plus data from other sources (notes of conversations, radio & TV programmes, and public events).

It showed again that ‘short-termism’ was a dominant concern. 60% of our leaders mentioned it.

‘Confused’ and ‘fear’ were volunteered by more than 48%. The next to be mentioned was ‘risk aversion’. Important new issues were ‘inclusivity and diversity’, and ‘purpose’ was also frequently mentioned.

Of significant importance is the fact that new themes emerged, led by ‘purpose’, and ‘inclusivity and diversity’, plus ‘overwhelmed’. Their appearance since 2016 reflects the fast growing awareness on these issues by a growing number of leaders, especially in the corporate sector.

This time, four out of our initial nine themes were not in the top 10: ‘fear of career-limiting moves’, ‘wilful blindness’, ‘reactionary mindsets’ and ‘denial’. (The latter two themes were not included in coding of the 26 themes, so they were not tested using our data.)

The difference in results is explained by two factors. First is the far-wider data sources included in the 2018 sample. Second is that some characteristics in the original conclusions in 2016 were subjective aggregations of impressions by the authors.

These phrases did not always fit neatly into the NVivo coding protocols, so were not coded for the NVivo data crunching process. This does not devalue what each phrase identifies. It does not mean it is no longer valid. It is a realistic acceptance that what makes a good descriptive cannot necessarily be matched in the data-coding process.

In conclusion, our analytic strategy facilitated by NVivo enabled us to refine and reinforce our initial hypothesis. We were also able to generalise our findings. Therefore we can be confident that the original subjective ‘hunch’ which catalysed this project from 2014 was largely correct.

The issues for leaders have become wider, deeper and more negative than in 2014 and our interim study in 2016. There are solid grounds to conclude that leaders continue to struggle and worry about their new vulnerabilities in this age of deepening disruption.

Despite a hectic speaking schedule, Nik was delighted to be able to continue the conversations sparked by his presentation in a series of workshops.

For information on events we’re attending or to find out more about TtU, sign up to our newsletter here or visit www.thinkunthink.org